You can dress as a “native” if you wanted to, but there are photo studios in Baguio where you wear a g-string and Ibaloi tapis with a pine forest backdrop. You can even wear a rattan headgear or a bungkaka, a bamboo buzzer which creates a buzz when you strike it on your lower palm. The Ibalois used it to drive away the devil except that in the 1920s, the devil was you.

Baguio was said to be the first cosmopolitan city in the Philippines. When the Americans built Kennon Road, they advertised all over the world and so got a international crew. In 1909, it was said that residents in the freshly-chartered city spoke 30 different languages.

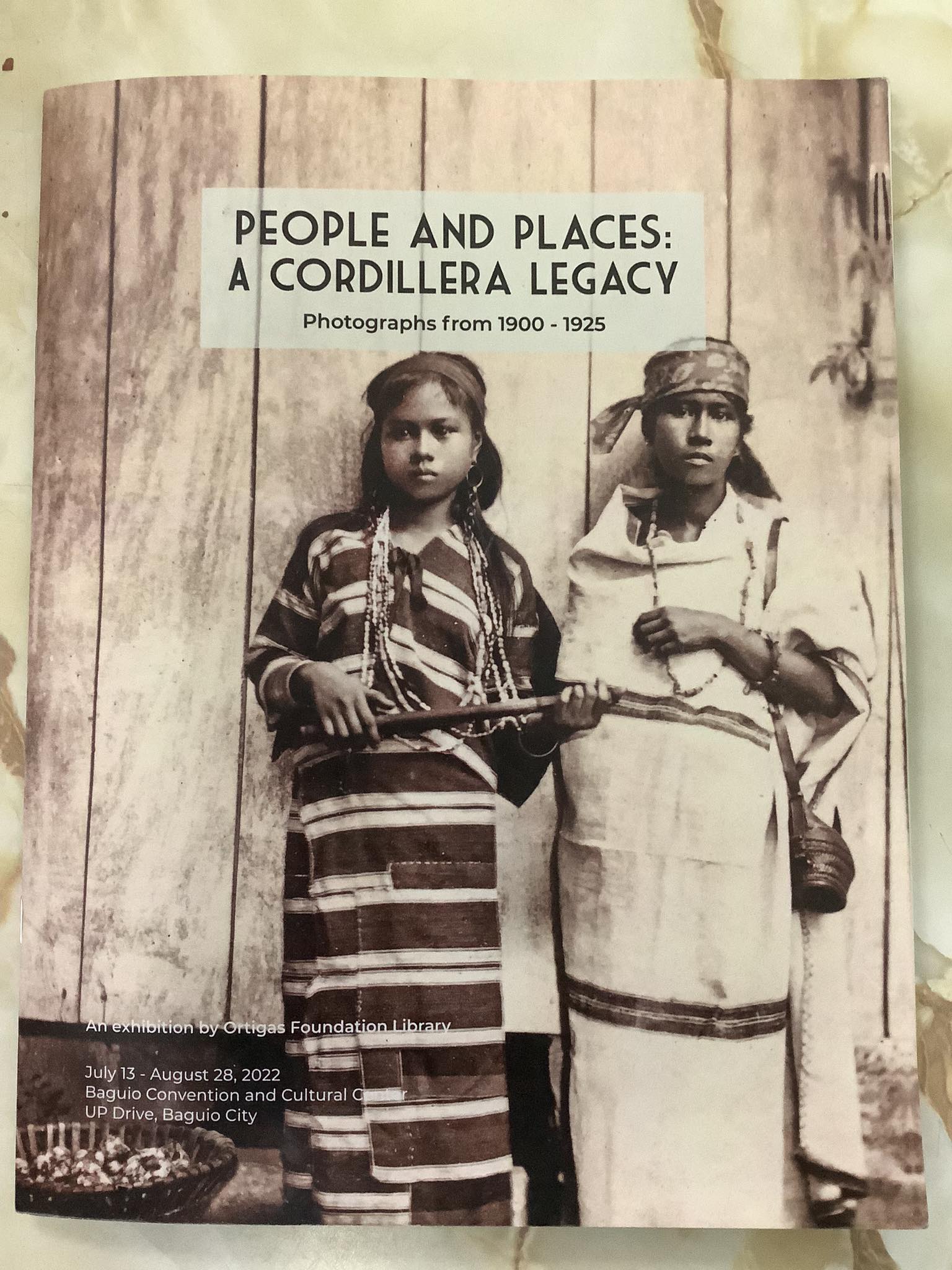

A new photo exhibit at the Baguio Convention Center brings you back to Baguio and the Cordillera from 1900 to 1925. These featured the photo collection of Jonathan Best and John Silva of the Ortigas Foundation Library.

“These images are only a small sample of the hundreds of photos taken in Mountain Province over a century ago by local amateur photographers, government officials and anthropologists, the majority of whom were foreigners from Europe and America,” said Best.

Some of the 111 photos here were taken by Dean Worcester (an anthropologist and Secretary of the Interior) and his assistant Charles Martin who went on to be photo editor of the National Geographic Magazine.

Eduardo Masferre, the most famous Cordilleran photographer, has yet to establish his commercial photo studio in Bontoc in 1934.

So most of the photos here are the Cordillerans in their fineries.

They are in black and white though some are hand-colored. Most of the “subjects” were so serious that their belief that the camera steals your soul might be true.

“Why do they look so sad,” Baguio boy John Silva asked during the opening. Because one, the posing can take minutes so holding a smile was torturous. Second, they don’t really know what these photo apparatuses were and what if they were guns? And third, they were not given copies so how would they know if they were photogenic?

When these photos were exhibited in Sagada last June, Silva said that one boy told him that their ancestors are now looking at themselves through their eyes.

Silva and Best said that they chose the photos that are not touristy, like those selling or grilling dogs or “headhunter” photos.

The photos I love in the exhibit (because I didn’t see often”) are the tourists themselves.

The secret to being a tourist in Baguio a hundred years ago is to stand out especially at your arrival.

One is a 1905 postcard of a “woman traveling in a sedan chair, Benguet.” Two Benguet men in G-strings carried on their shoulders two bamboo poles supporting a woman on a rattan chair. The woman was holding the favorite status symbol among Ibaloys at that time: an umbrella.

Another photo had this caption: “Lowland tourists driving an early automobile on the Benguet Road. c. 1920.”

It showed three tourists in ravishing coat and tie at the backseat of a Model T that just crossed a bridge on Kennon Road then known as the Benguet Road. Their driver was also in a suit but the “local tourists” had their noses up high.

Most tourists came up to Baguio during the Holy Week. But then they didn’t come here with bonnets, short shorts and tank shirts and flipflops like they do now.

“Well dressed Holy Week tourists in Baguio, March 26” had them wearing light-coloured slacks, summer coats, Italian hats, flapper heels, and silk scarves. One of the girls was carrying a large wicker basket supposedly for a picnic by the meadows.

One of the better lit photos has a Filipino tourist with the majestic Banaue rice terraces in the backdrop. He was holding a movie camera and a pistol.

What’s the pistol for, we ask 100 years later. A wild boar? An Ifugao warrior running amok? A murder mystery?

Coming to Baguio at that time meant riding the rails and then bringing your automobile up the rugged Benguet Road or riding a bus from the Damortis railway station. Only the rich can afford such trip to the “exotic” mountains. So before you arrive to Baguio, you have already arrived.