A LANDMARK study in Sweden delved into the quintessence of who a Filipino is. And the Cordilleran is the purest of them all.

The study, mainly funded by Uppsala University in Sweden has 53 authors and is titled “Multiple migrations to the Philippines during the last 50,000 years” The study investigated 2.3 million genotypes from more than 1,000 individuals (1,028) representing the 115 Philippines indigenous groups and the genome-sequence of two 8,000-year-old individuals from the Liangdao area in Taiwan Strait.

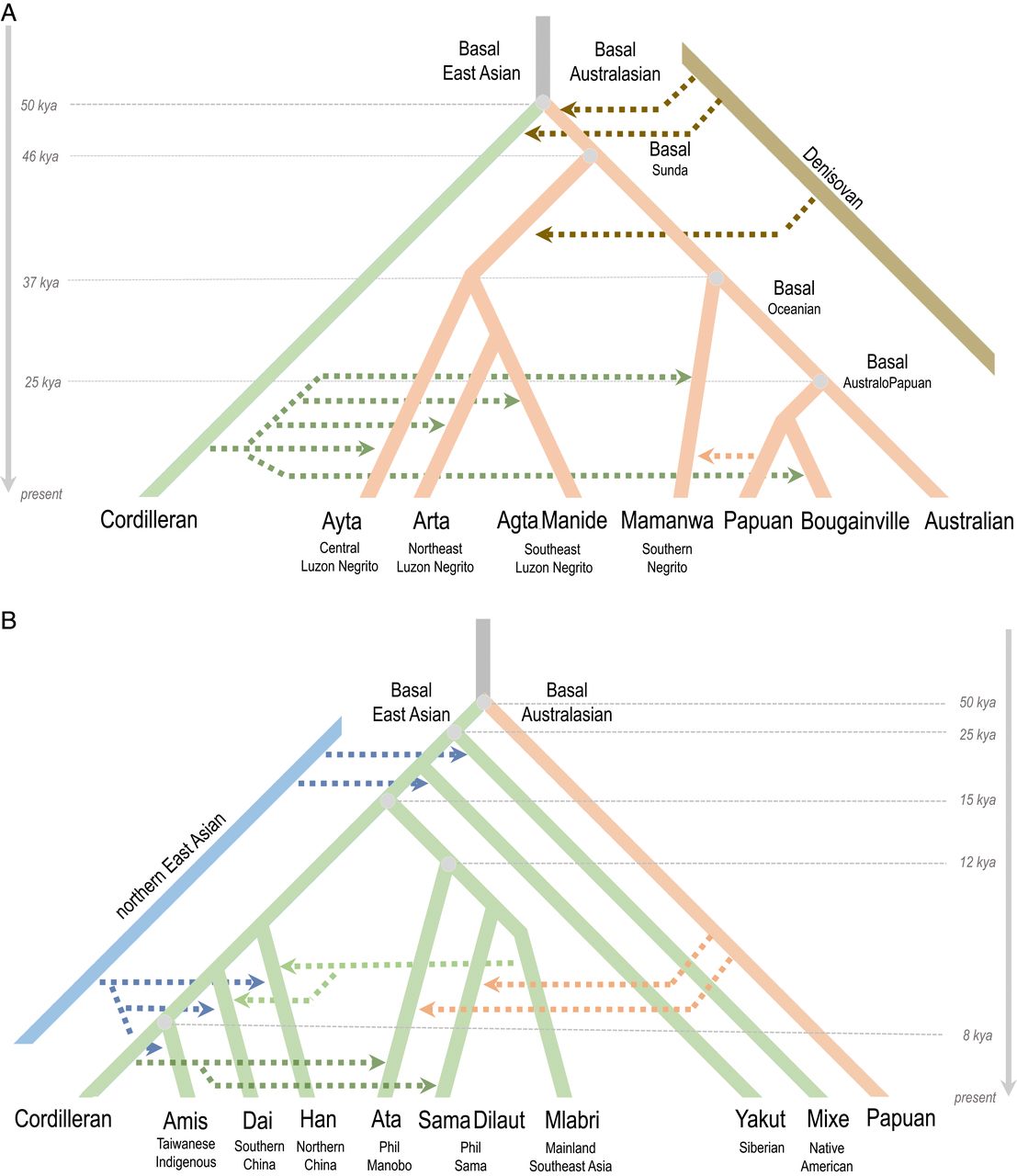

“We show that the Philippine islands were populated by at least five waves of human migration: initially by Northern and Southern Negritos (distantly related to Australian and Papuan groups), followed by Manobo, Sama, Papuan, and Cordilleran-related populations.”

The Cordilleran-related populations (Kankanaey, Bontoc, Balangao, Tuwali, Ayangan, Kalanguya, and Ibaloi) belong to the fifth migration which happened approximately 8,000 years ago.

But even before that, when the Philippines was still not the archipelago we know now, it was physically united.

“Until the end of the Last Glacial Period (∼11.7 thousand years ago [kya]), the Philippine islands were mostly contiguous as one large landmass, separated from Sundaland by the Mindoro Strait and the Sibutu Passage. Hominins have inhabited the Philippine islands since at least 67 kya.”

That was 67,000 years ago. A separate study in 2019 said that there were already “people” in the country at that time.

They are more known as hominin or any member of the zoological “tribe” Hominini (family Hominidae, order Primates), of which only one species exists today—Homo sapiens or human beings). These small-bodied Homo luzenensis (said to be forerunners of hobbits) lived on the island of Luzon at least 50,000 to 67,000 years ago. The hominin—identified from a total of seven teeth and six small bones—hosts a patchwork of ancient and more advanced features.

In 2010, Filipino archeologists unveiled the 67,000-year-old fossil in Callao cave in Cagayan, which they tentatively suggested belonged to a small-bodied member of Homo sapiens, making it perhaps the oldest sign of our species anywhere in the Philippines at the time.

But while further studies are needed for these hominids also known as Daenisovans, this new study looked at the later visitors.

“Our analyses indicate that the Philippines was populated by at least five major human migrations: Northern and Southern Negrito branches of a Basal Australasian group, who likely admixed independently with local Denisovans within the Philippines, plus Papuan-related groups, as well as Manobo, Sama, and Cordilleran branches of Basal East Asians. Cordillerans, who remain the least admixed branch of Basal East Asians, likely entered the Philippines before established dates for the agricultural transition and carried with them a genetic ancestry that is widespread among all Austronesian (AN)-speaking populations,” the Uppsala study said.

The study said that even among the Aetas, there are deep divergences. It said that the ancestors of the Negritos of Northern Luzon were the first to migrate to the Philippines, probably 46,000 years ago, probably through Palawan or Mindoro.

The study showed that the Southern Negritos like the Mamanwas have more in common with the Australo-Papuan genetic signal and appeared to be an offshoot, diverging about 37,000 years ago through Mindanao, likely via the Sulu Archipelago.

“Both Northern and Southern Negritos subsequently admixed with Cordilleran-related populations, and, interestingly, Southern Negritos received an additional gene flow from Papuan-related populations after Australian-Papuan divergence. This previously unappreciated northwest gene flow of Papuan-related ancestry had its greatest impact on eastern Indonesia, as well as ethnic groups of the southeastern Philippines, such as Sangil and Blaan,” the study said.

Next came the ancestors of the Manobos.

“The ethnic groups of the southern Philippines exhibit a ubiquitous ancestry that is non–AustraloPapuan-related and which is generally absent among non-Negrito groups of the northern Philippines. This unique genetic signature, heretofore designated as “Manobo ancestry,” is highest among inland Manobo groups of Mindanao Island,” the study said.

“In addition to Manobo ancestry, another distinct ancestry was identified in the southwestern Philippines. This genetic signal is highest among Sama sea nomads of the Sulu Archipelago and is designated as “Sama ancestry”,” it added.

Both the Manobo and Sama genetic ancestries diverged from a common East Asian ancestral gene pool and migrated here about 15,000 years ago.

The last to arrive are the Cordillerans, and unlike the other migrations which came from the South, the Cordilleran ancestry is more marked with the genetic make-up of the 8,000-year-old Liangdao individuals.

“The two individuals from Liangdao of the Matsu archipelago in the Taiwan Strait share the highest levels of genetic drift with Cordillerans, Amis, Atayal, and ancient individuals from the northern Philippines, Malaysia, Taiwan, and Lapita,” it said.

Given the location of Liangdao, close to mainland China (26 km and 167 km from Taiwan), the ∼7,000- to 8,000-y-old Liangdao-2 individual represents the oldest link of “Cordilleran” ancestry to mainland Asia,” the study added.

The ancestors of the Cordillerans probably migrated only about 7,000 years ago from mainland East Asia and Taiwan based on the genetic makeup of present-day Cordillerans.

‘This finding, taken together with the earliest archaeological evidence of Neolithic assemblages dated to ∼3 to 4 kya in the northern Philippines, suggests that the earliest Cordillerans were, like other groups in coastal East Asia at this time, complex hunter-gatherers rather than settled agriculturists,” it said.

Others probably migrated to Northern Luzon later, from the coastal China/Taiwan area and dispersing into Batanes Islands and coastal regions of Luzon.

But if the latter groups were largely agricultural, the idea of the agricultural Cordillerans was probably cultural rather than genetic.

‘Two contrasting models have been forwarded for the Holocene migrations into the Philippines. One is the out-of-Taiwan hypothesis, which espouses a unidirectional, north-to-south spread of the Neolithic package by ocean navigators from Taiwan, bringing with them the AN languages, red slipped pottery, and cereal agriculture. On the other hand is the out-of-Sundaland hypothesis, a complex south-to-north movement of population groups into the Philippines since the early Holocene, preceded by a maritime trading network, and by population dispersals from Sundaland following a climate change-driven inundation of previously habitable lands,” it said.

The study suggested that the gene flow of Cordilleran-related ancestry from the Southern China/Taiwan area into the Philippinesmay have occurred in multiple pulses after 10,000 years.

“The last three population waves occurred between 15,000 and 7,000 years ago — a period in which climate change caused geographical transformations of the region. Sea levels rose, for example. Sunda, until then a large, fertile land mass between Southeast Asia and Oceania, was inundated and the land bridge between Taiwan and southern China was submerged beneath the waters,” the press release said.

The study also said that although the genetic makeup of the Filipinos may be very diverse, the languages relatively are not. This is because of the dominance of the languages of the later migrants. The complex Negrito languages, for example, are now either dead or dying.

And after the major migrations, the admixture became the norm. Except among the Cordillerans.

“This geographic and cultural isolation may have played a role in the high linguistic diversity of the region and the low levels of genetic admixture displayed by some groups. In addition to the previously reported Kankanaey, and following admixture and combination of f3 admixture and f4 statistical analyses, we found Bontoc, Balangao, Tuwali, Ayangan, Kalanguya, and Ibaloi as being among the least admixed populations bearing Basal East Asian ancestry,” the study said.

“Moreover, formal tests using f3 admixture and f4 statistics provide direct evidence that Central Cordillerans retained to be the only ethnic groups within the Philippines who did not receive gene flow from Negritos. This is unexpected, given the series of migrations and periods of colonization in the surrounding area of the Cordillera region and the documented records of trade and historical interactions with Negrito and non-Negrito groups of Luzon,” it said.

So the independent spirit of the Cordillerans may have been in the genes after all.