THE Philippines is located 1200 km north of the equator and thus is at the center of the Pacific Typhoon Belt, and because if its location and warm waters is hit by some 20 typhoons every year, ‘storming,’ so to speak, news headlines with stories of disasters left in the trail of these tropical cyclones – lives lost, structures destroyed, hundreds injured, and communities suffering from landslides and destructive floods.

But because of the frequency of these occurrences and despite the severity of damages, these events pass into oblivion, or become mere data in the spectrum of disasters caused by extreme weather events – wet that kills and dry just as deadly. The incidents are almost on a daily basis happening in scattered portions of the world that they become just passing headlines in local and international news. It has been decades since climate change has come to the fore as a worldwide emergency issue, but the science of what has been causing it – greenhouse gas emissions for one, is hardly understood among grassroots communities most affected by climate change.

Studies on how to confront climate change and reduce carbon footprints are largely lodged in highly technical debates in a language that is foreign to the greater masses, but well understood by a privileged circle of industry players.

While climate change is not denied as perhaps the biggest threat to Earth’s survival, the world is turning to bracing itself from its onslaught, and in addressing carbon footprint to ease the intensity of extreme weather events. In the wake of this effort, world thinkers, experts, planners, scientists, – and yes, industry leaders – have popularized the concept of ‘green transition.’

Green transition

Green transition denotes a shift from old ways of doing things to a more economically sustainable growth. It entails the prudent consumption of natural resources and an economy not based on fossil fuels. It is the time needed for humans to make changes so that they do not endanger the planet to a point that it is irreversible and will jeopardize the future.

The 2020 Agenda, as a result of the Paris agreement has more than a hundred plans on how to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and prevent global temperatures from rising more than 15 degrees Celsius.

In daily living, green transition in small ways can be just practicing environmentally friendly ways of doing things. But technology plays a big role too which can include replacing fossil oil heating and shifting to electric cars.

And here lies the threat against indigenous people.

Indigenous people and IKSPs

The last frontiers of biodiversity and abundant natural resources thrive in the domains of indigenous people. This is what Vicky Tauli-Corpuz, former UN Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous People, says. “They have the least carbon footprints but are the most vulnerable to climate change disasters,” she said.

Vicky Tauli-Corpuz , executive director of Tebtebba and co -founder of Indigenous Peoples Rights International

She explained that indigenous people, simply by gazing at nature, the changing of seasons and cosmic phenomena, have learned to live in harmony with nature that form their indigenous knowledge systems and practices (IKSPs), the secret to the abundance of their natural resources. It is a way of doing things that can best be described to be guided by the words of Chief Seattle, an old Native American leader, who said, “We do not inherit the Earth from our ancestors, we borrow it from our children.” Thus, the indigenous practice of taking only what you need for the moment which resonates with a green transition principle of avoiding overconsumption of natural resources.

Which, sadly, in reality and in the practice of industry moguls, is in total contrast with this wisdom of ancestors.

The downside of green transition

Joan Carling, a UN Champion of Earth awardee, echoes the sentiment of Tauli-Corpuz, “Indigenous people are in the frontline of the impact of climate change but have the least carbon footprint.” She adds, “The issue of climate change is a global crisis severely affecting the rights and well-being of IPs across the world especially in relation to our rights to our land and territories and resources. Take the Philippines, here (the Cordillera region), for example, it is the indigenous people most affected by the landslides, the typhoons, because they live in isolated, remote areas with the least access to social services and exacerbated by the digital divide.”

But the other side of the story is the solutions provided are also adversely affecting us. This relates to the green transition, she continues.

An IP herself of Kankana-ey ethnicity of Mountain Province, Carling says of green transition, “It only exacerbates the prevailing inequity and discrimination. Because the imposition of solar farms, windmill farms, dams, are also taking away our lands and destroying our resources. Because this energy is created not for us, it’s for urbanization, industries, tourism – that’s one, but also it is destroying the environment.”

“So while we support that we need to shift from fossil fuel to renewable energy, to reduce carbon emissions, it cannot be in the context of business as usual because as we speak for example families in India are protecting their eviction to give way to a solar farm.”

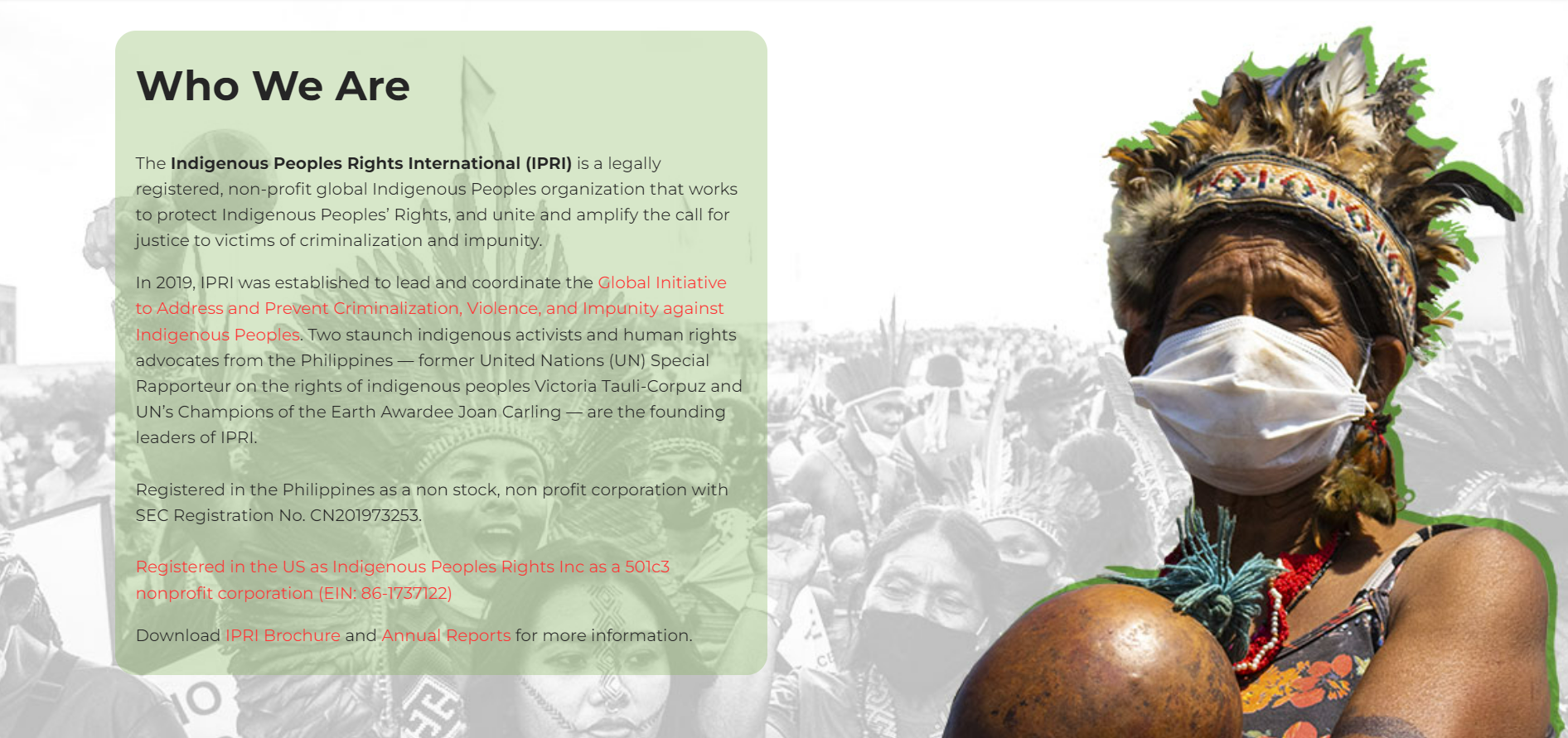

The Indigenous People’s Rights International (IPRI), a global organization that works to protect IP rights and amplify the call for justice for victims of impunity, of which both Carling and Tauli-Corpuz are founders, is actively helping fight for the rights of affected communities in India where some 50 solar projects with a combined capacity of about 438 gigawatts have been approved by authorities. Where the sun-powered farms are already in operation, both the Bhadha and Pavagada solar parks, researchers have found the all-too familiar tales of broken promises told by affected villagers.

An article by The Conversation, Oct. 11,2022, on the Pavagada solar park says, “The model of the future ran into problems of the present. Our five years of interviews and fieldwork with village women, community representatives, farmers, local government officials, solar company managers, and renewable energy authorities clearly showed the Pavagada model wasn’t distributing benefits evenly. The energy transition left winners – and losers.

Who won? Larger landowners. Who lost? The landless. Over half of the 10,000 people in the five villages near the park are landless agricultural workers, as is common in much of rural India. Because they do not own land, they receive no income from the leasing model. And with much local farming land leased to the solar park, many landless labourers lost their livelihoods.

Those worst affected were more likely to be women, particularly those from lower castes or Adivasi (Indigenous) backgrounds. This is because their financial independence came solely from agricultural income.”

It’s a story that echoes in many lands occupied by poor communities and by indigenous people.

The bigger problem of green transition is the mining of transition minerals – nickel, lithium, cobalt, all of these, Carling said.

There is a high demand for all these minerals to support the development of production of electric cars, of solar panels and all these needed for renewable energy. So that’s a big problem because more than half of the deposits of transition minerals are in indigenous territories so we will again be put in a situation where our resources will be taken away in the name of climate change solutions or in the name of green transition, Carling said.

Carling further laments that it will in fact be green colonialism if it is again imposed on IPs that will just destroy the livelihood and sustainability of their territories for the next generation.

“So that’s a big problem and there’s not much knowledge yet on this. For us, we are becoming like a voice in the wilderness because donors, investors, are all out to support the green transition but they’re not looking into the sustainability and social equity dimension. And it’s again in the context of business as usual, wherein the drive is within the unsustainable pattern of production and consumption,” Carling said.

Carling cited the popular demand for electric cars and vehicles. “But who can afford electric vehicles? What ordinary people need is an effective mass transport system. So funding, investment should go to subsidize mass transport, develop it efficiently instead of producing more e-cars that will demand more transition mining.”

Carling echoed the sentiment of the indigenous communities in Palawan where some nickel mines are operating and communities are protesting. There is worry over allegations that the IPs there, who insist that their rights are being violated by the mining of nickel, cannot seek a dialogue with National Commission on Indigenous People (NCIP). In June of this year, however, the NCIP MIMAROPA suspended the Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC) process of Ipilan Nickel Corporation in response to complaints lodged by the Palawan indigenous communities in the ancestral domain at Brooke’s Point involving allegations of P300,000 bribery to individuals to sign documents.

Carling said mining for “transition minerals” operate in many countries like Russia, Argentina, Chile, Costa Rica, among others. In Asia, for nickel, it is Indonesia and the Philippines where there are significant deposits of nickel.

Both Tauli-Corpuz and Carling, as IPRI directors, have also signed a letter addressed to Elon Musk for his company Tesla, which produces electric cars, to stop buying products from NorNickel, a company they claim to destroy indigenous lands in the Russian Siberia and to resume trade with the company only if it implements the requirements of the local indigenous communities with regard to a healthy environment.

Voices in the wilderness can also be heard

But there are success stories to speak of when indigenous people come together and rights organizations help them.

Take the case of windmills in Norway where turbines were built on the land of the Sami, the Artic’s circle native peoples. The Sami people had suggested for the windmills to be built elsewhere because Norway is a big country and not on their land as it will affect their reindeer herding which is part of their culture, their being Sami, their identity. But the government gave them the permits and in the winter, when the wind turbines were turning, there was not a reindeer in sight. Reindeers roam in search of lichens, their source of nutrients, and have come by tradition on the Sami winter grazing grounds, which stopped as the turbines scared them. So the Sami filed a case in court, and won, on the premise that indeed the windmills deprived them of the right to enjoy their own culture. But the windmills continued to operate more than 16 months after the Norway 2021 SC decision. The youth, led by environmental campaigner Greta Thunberg and hundreds of other activists rallied at the entrance of the energy ministry against the windmills. Thunberg, an advocate against carbon-based power, said the transition to green energy cannot come at the expense of Indigenous rights.

“Indigenous rights, human rights, must go hand-in-hand with climate protection and climate action. That can’t happen at the expense of some people. Then it is not climate justice,” Thunberg said.

IPRI gave a statement of support to the Sami people addressed to the prime minister of Norway. “The Sami youth did a demonstration in front of the petroleum and energy ministry and they were arrested. I mean physically removed. But then it ignited a big debate in Norway and more people joined their protest. And the prime minster had to apologize publicly for that,” Carling said.

Carling also cited another windmill case in Kenya where the indigenous people won to be paid the proper compensation for the use of their land.

Green transition presents a precarious balance between the battle for fighting for indigenous rights and the necessity to shift to fossil-free energy.

A letter initiated by IPRI and signed by many rights and indigenous groups to the UNFCC & State parties at COP27 appealed to have human rights at the center of climate action.

In the October 2022 letter, it was cited that the race to a decarbonized economy by 2050 should not disregard the rights of local communities and Indigenous populations, “in particular those impacted by the boom in the extraction of the minerals needed for the transition, and by land-intensive renewable energy projects.”

According to the letter, there have been 495 allegations of human rights abuses in relation to transition minerals mining since 2010. “But it will also continue to fuel opposition, conflict, and result in delays to both projects and achieving our global climate and Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) targets. Such conflict has already resulted in at least 369 attacks on human rights, labour and environmental defenders around the world since 2015, including 98 killings, related to renewable energy projects, and 148 attacks, among them 13 killings, related to transition minerals mining,” the letter stated.

The grim situation calls for the importance of companies to work closely with indigenous communities when doing their projects.

In the Cordillera region, where mining and dams are always potential projects, Carling warned that the indigenous communities must remain vigilant so they will not have to sacrifice their rights in the name of green transition. “Green transition must be viewed in a transformative way, where win-win policies are part of the business,” she said. IPRI is still hard at work in pushing for justice for indigenous people by submitting position papers on what should be in the laws in countries where they work when it comes to the rights of indigenous people with the key demand to respect their rights to their land, territories and resources.

She said that even dams built in the Cordillera, which is host to major headwaters, can be disastrous because of siltation it causes upstream and flooding downstream.

Tauli-Corpuz said, “ While the green transition is the right approach to lower carbon emissions, it is important to ensure that human rights based approach guides its implementation, including rights of indigenous peoples. Renewable energy projects in their territories must have free, prior and informed consent and their right to determine the role of their forests must be respected.”

-30-

This story was produced with support from the American Bar Association.