Erlyn Ruth Alcantara

THIS paper is to be delivered at the Commemoration of the Birth Centenary of William Henry Scott, an online conference on July 24, 2021, led by the National Historical Commission of the Philippines (NHCP) and the University of the Philippines Baguio (UPB) as part of the 2021 Quincentennial Commemorations In The Philippines

This is nothing close to an academic paper. It is more of a remembrance of Scotty as a dear friend and neighbor, what Sagadans call sagugong. But he was really so much more than a neighbor. He is a son of Sagada. During and after his political detention under the Martial Law regime, Sagadans proudly avowed, “He is one of us. He is our kinsman. “Ib-a mi na.”

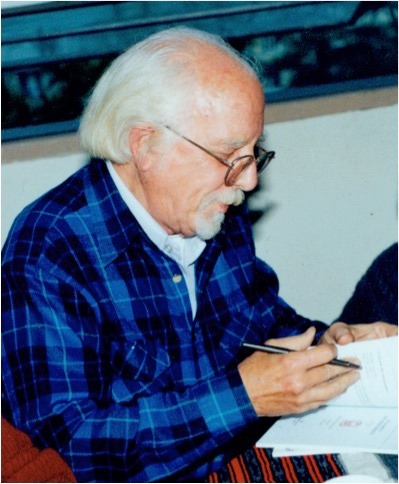

Scott always believed that his missionary vocation was “to put down roots and flourish by strange waters.” And flourished, he did. What he left behind was a legacy. A bibliography of his works compiled by eminent scholar Harold Conklin lists 240 titles comprised by ten books and monographs, nine edited collections of his own and others’ essays, 170 articles, chapters and reviews, and numerous translations of unpublished Spanish documents.

This exceptional scholarly work combined with his personal achievements is a legacy that only Scott could have achieved.

He was a professor in Church history, Chinese history, Philippine history and taught at the University of Santo Tomas, St. Andrew’s Theological Seminary, Trinity College, and the University of the Philippines. He had the distinction of being the only alien citizen to teach Philippine history at the U.P.

It was at the state university that he found idealistic young students making thought-provoking statements about the national conditions at the time and was impressed by their willingness to be struck down by truncheons or be shot in the streets. His contacts with activists inside and outside the classroom inspired him to respond to the issues being raised and he considered a courageous exchange of ideas the most fruitful teaching situation.

But after the declaration of Martial Law in 1972, this attitude was considered unacceptable by the president of Trinity College, and Scott was abruptly dismissed. He was arrested and delivered to political detention on New Year’s Eve, 1973. Confiding in Philippine justice, he declined the interference of the US Embassy, but the military ruled for his deportation. He was accused of being an undesirable alien and was given a public hearing. Lawyer Sedfrey Ordoñez volunteered to defend him.

The hearing turned out to be a tribute to Scott by people who knew him as a scholar, teacher, writer, historian, and musician. Scholars put on the stand acknowledged his vast contribution to Philippine historiography and ethnography has given Filipinos the chance to gain a deeper understanding of our cultural heritage and destiny as a people. Testimonies from bishops, priests, and colleagues, and petitions from faculties, student bodies, and citizens’ assemblies were presented. Those from Igorots on the Cordillera honored him as their own son and regarded him as a tribute to the Christian faith he professed. His life’s work and true worth were weighed in the balance and not found wanting. “He is our kinsman. Ib-a tako na.”

In May 1973, the Commission on Immigration and Deportation ruled that the prosecution had failed to prove its accusations and Scott was released immediately. On his return to Sagada, he was surprised to be met by a huge crowd who stopped the bus at Nangonogan. He recalled to me an unusual gesture from one of the Sagada men there to meet him. Holding Scotty’s shoulder firmly, this neighbor launched into a welcoming chant, a wailing cry, and a prayer all at once, in one big extraordinary burst of sound. The cheering crowd carried Scotty on their shoulders as they marched into town, teary-eyed but overjoyed at welcoming a son back home. “He is one of us and he has come back home. Ib-a tako na.”

To celebrate his 100th birthday, I suggest we go to our cupboards or a nearby coffeehouse and order a bottle of San Miguel Pale Pilsen and eat cake. This was a Sagada afternoon ritual that he insists I invented. But I couldn’t have because I don’t particularly like fluffy cakes, being more of a cookie person (in more ways than one ); it was two things he liked – cake and beer — so it sort of invented itself. So yes, let’s eat cake and have a San Miguel Pale Pilsen and drink to him. Cheers, Scotty!